The legacy of CORE: Syracuse’s Urban Renewal Protests, 60 years Later

Sixty years after the CORE movement shook SU's campus, Syracuse looks to undo the harms of urban renewal that sparked the 1963 protests. Cassandra Roshu | Photo Editor

Get the latest Syracuse news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe to our newsletter here.

This story is the second installment in a two-part series. To read the first installment, click here.

The professor

When George Wiley arrived at SU in 1960, he found a city deeply segregated, even as urban renewal policies sought to rebuild it from the ground up.

By then, Wiley had only taken his first tentative steps into activism. As his trademark Austin-Healey convertible rolled into town, he couldn’t have known that Syracuse, where he hoped to establish himself as a renowned chemist, would instead launch him to the forefront of the Civil Rights Movement.

Informed by his Rhode Island childhood, Wiley was as preoccupied with the insidious, unspoken discrimination of northern cities as he was with the boldfaced racism of the south. Wiley observed how Black Syracuse residents were segregated not by explicitly racist policies, but through economic disenfranchisement and bureaucratic maneuvering, even as their elected officials outwardly championed equality.

“Though conditions in the South are often more gross and extreme, the deep-seated, hard-core problems of the northern ghetto are much less tractable, much more difficult to define or identify, and thus considerably more frustrating,” Wiley would later say, according to the Kotzes’ biography of him.

That perspective, forged by his work in Syracuse, would fuel Wiley’s meteoric rise to the national stage. He later became second-in-command of CORE’s national leadership before forming his own group, the National Welfare Rights Organization, whose aggressive campaigning earned him a spot on President Richard Nixon’s infamous list of personal enemies.

All that would come much later. By 1963, two years after signing on with the Syracuse CORE chapter, Wiley was still at the inception of his civil rights career, a career he balanced with groundbreaking chemistry research and a newborn child. By then, he had ceded the chapter’s leadership to Bruce Thomas, a Black factory worker-turned-activist, but he remained its founder and public face.

From its earliest days, Wiley’s campaigning drew ire from university leadership.

“The university was extremely unhappy with George and me and the other students,” said Edwin Day, who worked closely with Wiley for much of his career. “Because it was mostly students from the university, mostly graduate students who were the leaders.”

Wiley led his protests from the front lines. During the urban renewal demonstrations, police arrested him in full view of television cameras, tackling the polished professor onto “bricks and rubble” as they twisted his arms behind his back. Wiley’s rough treatment rallied his supporters as he spent days in Willow Street jail, next appearing in public with his arms bandaged.

By the time Wiley returned to the streets, early talks had begun between Mayor William Walsh and civil rights leaders, including those from CORE.

At issue was Walsh’s proposed fix to the city’s rampant housing discrimination: the creation of a human rights commission, which the mayor said would review cases of housing discrimination, forwarding those it deemed worthy to a state-level committee for further action.

Wiley scoffed at the idea. He argued such a commission would amount to a “toothless, lifeless” entity, unable to enact meaningful change. If the city was going to create a commission, he reasoned, it should be able to subpoena landlords and enforce its rulings. Walsh refused, arguing it was beyond his authority to grant those powers.

When talks failed on Thursday, Sept. 19, a “runner” reportedly brought the news to the picket lines, signaling for demonstrators to begin occupying demolition sites. In the clash that ensued, police arrested more people than on any other day of the protests.

CORE extended an olive branch that weekend, acknowledging the mayor’s commission was “a skeleton which could provide a fruitful basis” for meeting the group’s demands.

On Monday, Sept. 23, Walsh and a team of civil rights leaders came to an agreement: the mayor would slow the commission’s implementation as activists lobbied to strengthen it, and in return, protesters would halt acts of civil disobedience. The fight had moved from the streets to the mayor’s office.

In meetings, Wiley approached issues like housing integration methodically, through a scientific lens. He made his case for civil rights policy with maps and statistics, which he toted to discussions with city leaders and activists alike. He was adamant about pursuing concrete policy change, with little patience for empty promises or political rhetoric.

This put him at odds with Walsh, who was moderate in his approach to civil rights but all in on the promises of urban renewal. Their meetings became heated as Wiley, Walsh and their respective allies sparred over policy proposals, with debates sometimes descending into personal attacks.

Membership on Walsh’s planned human rights commission became a key issue. Civil rights leaders wanted guaranteed seats for their supporters. Again, Walsh refused.

“You are talking about a commission you appoint and you control and we are not having any part of,” Wiley said. When the mayor assured him the commission would include leading members of the community, Wiley replied that the civil rights organizations needed seats to “prod the leading citizens and keep them in motion,” according to the Post-Standard.

After a week of negotiations, some points of compromise emerged. Walsh agreed to advance an ordinance banning discrimination against Black homebuyers and conceded that the city should engage in a scattered-site public housing program, meaning public housing units would be dispersed throughout the city rather than condensed in a single area. He also promised to go on TV to promote the human rights commission — whatever form it might take — and to invite bankers and realtors to a meeting promoting fair housing.

Some organizers expressed confidence, believing they’d made headway. But Wiley, who continued traveling daily between the picket lines, negotiations with city officials and nightly meetings at local churches, was more pessimistic.

“It doesn’t seem to me we have made much progress,” he said as one negotiating session drew to a close, according to the Syracuse Herald-Journal.

He may have been right. On Sept. 30, the city’s Common Council — at Walsh’s behest — established the proposed human rights commission without any enforcement power.

The chancellor

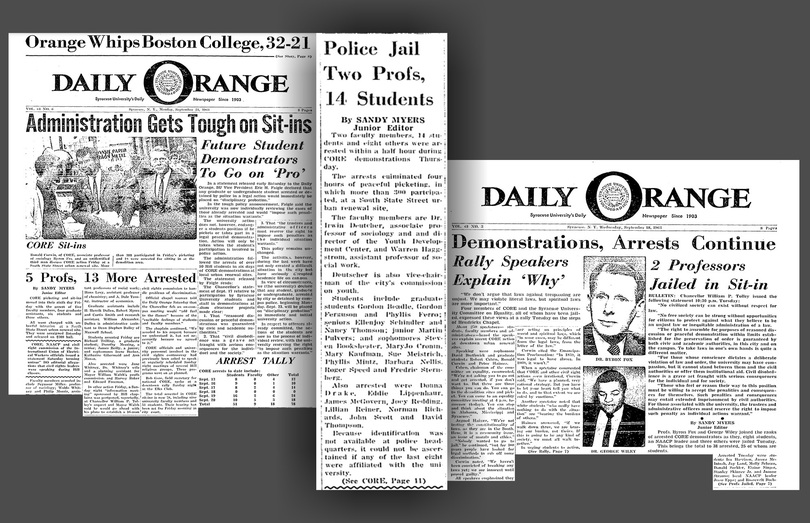

As picketing at the urban renewal sites continued, the protesters’ fervor was spreading up the hill, onto SU’s campus.

Demonstrators walked between classes with black-and-white CORE buttons pinned to their shirts. Sympathetic professors invited them to speak during lectures, and they hosted regular recruitment rallies on the steps of Hendricks Chapel. At least once, a CORE “sound truck” passed by campus, as unverified reports came in of protesters deploying bullhorns in university buildings.

William Tolley, SU’s chancellor, was caught in the firestorm.

Tolley was torn. One of his star professors was leading students in acts of civil disobedience that were plastered across the evening news. Dueling opinion pieces in the city’s newspapers alternatively lauded their bravery and slammed them as disruptive and out of control. The flood of letters that arrived daily at his office from parents, colleagues and community leaders were just as divided.

At first, Tolley tried to appease both camps. In a vague initial statement, he declared that the university was sympathetic toward the demonstrators, but that it nonetheless reserved the right to punish students “as individual actions warrant.”

Arrests continued. Pressure mounted. On Sept. 18, the Syracuse Herald-Journal reported that major donors were threatening to cut off contributions to SU, right as the university was mounting a massive fundraising campaign.

The chancellor’s stance against protesters quickly hardened. Days later, the university handed down a new decree: any students arrested by police or campus security would face immediate disciplinary probation. No exceptions.

By then, though, Tolley had gotten a reprieve, as CORE suspended the acts of civil disobedience that were getting students tossed in jail. The first real test of his hardline policy didn’t come until the Common Council established Walsh’s weakened human rights commission against the organizers’ wishes, and protests moved from the urban renewal sites to downtown Syracuse.

On Oct. 1, over 125 people marched in front of City Hall to decry the decision. Two groups of demonstrators, one after the other, blocked the entrance to the mayor’s office. City officials were seen stepping over demonstrators — including Malchester Reeves, the Black supervisor of the 15th Ward — to get inside.

Police arrested both groups. Their ranks included at least two SU professors, five graduate students and one undergraduate. Also among them was Wretha Wiley.

In a statement to the Post-Standard, SU officials held firm, reaffirming that any students arrested would face immediate disciplinary probation. The paper reported that SU security officials obtained the names of those apprehended and checked them against university records.

But backlash was building to Tolley’s crackdown. SU professors, colleagues at other universities and students’ parents flooded his office with letters, condemning the perceived violation of academic freedom. Statements of protest had also landed on his desk from a group of graduate students, the ACLU and the American Association of University Professors, whose membership included a large number of SU professors at the time.

Once it became apparent the protests were over, SU began to backpedal. A university spokesperson soon told the Herald-Journal that only the lone undergraduate arrested at city hall would face immediate probation.

In the days that followed, the Committee on Equality, an SU student organization that supported CORE, picketed Tolley’s office. Some students donned black armbands to “mourn the death of the freedom to dissent on campus.” After a meeting between SU officials and the group’s leadership, which included Howard Messing, Tolley informed the University Senate that SU wouldn’t punish any protesters until their cases were resolved in court.

In the address, Tolley framed his response to the protests as an attempt to balance the competing demands of academic freedom and campus stability. He claimed the disciplinary probation decree was “a preventative, not a punitive, measure” meant to dissuade protesters.

“The ingredients of uncontrollable mob action and violence were present and the danger was real,” he said.

Later that year, a judge dismissed charges against all but one of the 98 protesters arrested during CORE’s campaign. By then, Tolley had already granted “general amnesty” to all student demonstrators. In a statement quoted by The Daily Orange, he pledged that “external influences played no part in any of the decisions.”

Cassandra Roshu | Photo Editor

Meanwhile, the demonstrations against urban renewal had lost their momentum. On Oct. 2, after five more arrests, CORE and its partners issued a joint statement announcing their conclusion.

“The focus of our actions in the future will be expanded to other parties in the community which have been and still are participating in Syracuse segregation,” it read.

Progress through Walsh’s new commission seemed unlikely, and there were plenty of other battles to wage.

The 15th Ward came down. CORE, and Wiley, fought on elsewhere.

The aftermath

Sixty years later, CORE’s warnings about the impacts of urban renewal — the ones Wiley laid bare in his maps and statistics — have proved prophetic.

The measures Walsh implemented in response to CORE’s campaign failed to steer the city toward housing integration. Displaced Black residents continued to face a housing system rigged against them, with many rerouted back into impoverished neighborhoods built in the shadow of Interstate 81.

In November 1963, CORE submitted 27 allegations of housing discrimination to the city’s newly minted human rights commission. The commission turned them down, having ruled it possessed no authority to accept housing discrimination claims.

Meanwhile, police and politicians in the city cracked down, sometimes violently, against Black Syracuse residents. According to the Kotzes, rumors percolated of FBI surveillance against Syracuse CORE.

The city’s stubbornness and his mistreatment in the Willow Street jail left Wiley both embittered and motivated, the Kotzes wrote. In 1964, he left SU to pursue civil rights work full-time.

To this day, Syracuse’s Black residents remain concentrated in areas with poverty rates double that of the city’s predominantly white neighborhoods. The demolition of the 15th Ward and the construction of I-81 have since become symbols of the era’s failed urban renewal policies, and a focal point for policymakers seeking to reverse them. President Joe Biden, who graduated from SU’s College of Law in 1968, has cited the highway as a disastrous project that tore communities apart.

Now, half a century after his grandfather approved razing Black neighborhoods to make way for the highway, Mayor Ben Walsh is moving to tear it down, with plans to rebuild the demolished 15th Ward in its footprint. The project has been hailed as a victory for racial justice, though some residents who live near the viaduct have raised fears it will replicate the mistakes of urban renewal: dispossession, displacement and abandonment.

Wiley wouldn’t live to see his predictions come true, however. In 1973, at the peak of a civil rights career he launched on the streets of Syracuse, he fell overboard and drowned while boating with his children on the Chesapeake Bay.

The students who protested alongside Wiley and CORE have long since graduated, moved away and grown old. Several have died in recent years. In their online obituaries, between hobbies and career accomplishments and lists of surviving family members, there are oblique references to their involvement in some civil rights protest or another back in the day.

Of the protesters Barbara Nellis has kept track of, several found ways to continue their activism beyond Syracuse, she said.

After the demonstrations ended, Messing was arrested while doing civil rights work in Louisiana. The experience motivated him to return to SU as a law student, after which he took his first “real job” as a public defender.

Day remained at Wiley’s side for much of his career. He followed the former professor to New York City in his new role for national CORE, returning with him to Syracuse in 1965 to spearhead protests against the Niagara Mohawk power company. He would later help Wiley form the organization that spawned the NWRO in Washington, D.C., and was among those who spoke at his funeral, addressing the crowd of activists, organizers and politicians who packed the pews.

Nellis landed in Chicago, launching a career in journalism. She worked for 30 years at outlets including Playboy magazine and the Chicago Tribune.

For decades, Nellis didn’t return to Syracuse. When she visited a few years ago, she found a city greatly changed, the neighborhoods where CORE protesters picketed replaced with hospitals and parking lots.

She said she can’t help but see the irony of the city tearing down the highway whose construction helped spark those protests, all these years later.

The fall of I-81, along with the current political climate, has left her and other protesters wondering: after all those demonstrations, all those arrests, what did they actually accomplish?

“I don’t think we thought we could fix the world,” Nellis said. “We thought we could make it better. And we did a little bit. And then of course we’ve got now, where it looks like we didn’t make any difference at all.”

Her feelings, like those of Day and Messing, are mixed.

They recognize the gains of the civil rights movement and organizations like CORE, yet they fear the country is backsliding. They see the same hatred that upheld segregation in Syracuse as a factor in today’s politics, just manifested in different ways and toward different groups.

“We certainly didn’t stop urban renewal,” Messing said. “We certainly didn’t raise the thoughts of the average person in Syracuse or even on campus. But it doesn’t mean it’s not a good fight.

“I don’t think there’s any question that the fight is worth it. And it’s got to continue.”