R

ead grew up in his grandparents’ house with his sisters in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. His mom, a single parent, worked two jobs and could hardly afford food, clothing and shelter for her children. Read moved in with his grandparents when he was about 6 or 7. He never had a relationship with his father.

Watching basketball games on TV late at night with his grandparents spurred Read’s interest in sports. His grandfather worked in a factory, and his grandmother operated the family-owned bar. They provided for the family but that left Read and his sisters to handle themselves at times.

“We had everything all the other kids had, which before that we didn’t,” Read said. “But because of that, I didn’t necessarily get the structure or the discipline that I needed to be able to have.”

He only raised his grades in time to be eligible for sports. He’d sometimes skip academic classes to spend several periods in gym class. He’d get Cs on surprise tests, but kids who paid attention received Ds. Each report came back with the same comment: Extremely smart but doesn’t apply himself.

“You can do anything you want to do,” Read’s grandmother, who he called mom, told him. “You just won’t do it.”

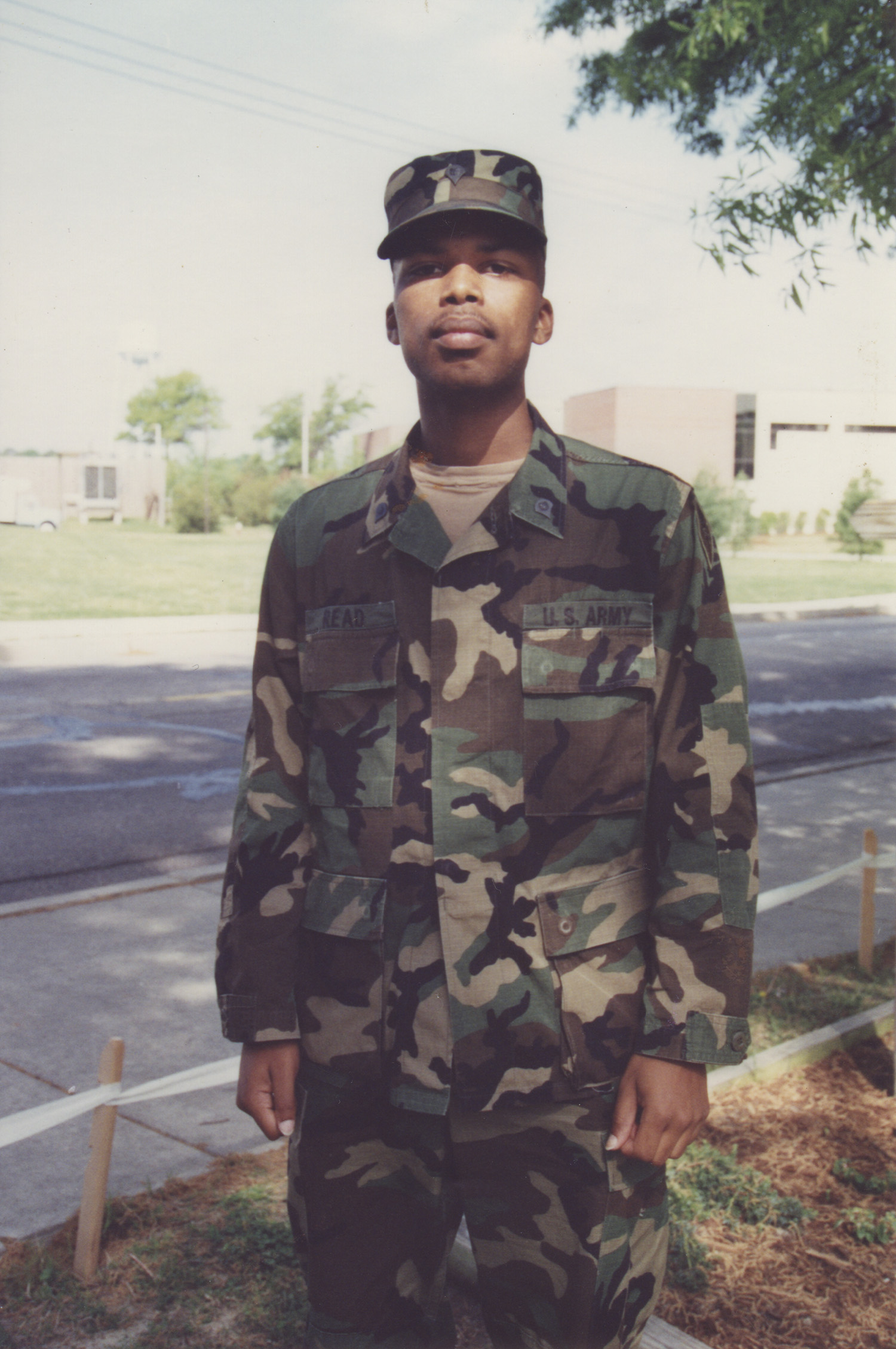

He decided late in high school he wanted to go to college and joining the military was the only way he could afford it because of the G.I. Bill.

Read eliminated the Navy because he couldn’t swim, the Air Force because flying planes required more smarts than he thought he had and the Marines because they were “definitely going to war all the time.”

“The army was the safe and easy bet for me,” Read said.

His grandmother also wanted to make sure Read stayed out of trouble. Shipping him off to the army became a way to do that. “Either you get right or you get out,” was her saying.

The Army sent Read to the cold weather training unit at Fort Drum. Within two hours of landing on the base, he joined his unit in the field on what Read remembers to be a minus 20-degree day. They handed him his equipment, including a Gore-Tex jacket, boots, several pairs of gloves and hats. He’d wear multiple hats and gloves at a time. It was all white instead of the standard Army green because he trained in the snow.

Roughly 80 percent of the unit’s time was spent in the field, Read estimates. Its motto revolved around the idea that the colder it was, the more the unit should be outside.

The soldiers slept in tents with just a mat to create a layer between the ice and sleeping bags. Heaters warmed the tents but would sometimes break.

They ran 6-7 miles each day, the sweat freezing into a solid chunk on the inside of their facemasks almost as quickly as it was produced and making it impossible to see.

A new private from Florida joined the unit and didn’t show up outside for formation his first day amid a blizzard when the unit took roll call.

“‘We go outside in this weather?’” Read remembers the soldier asking. “Yes, that’s what we do.”

Three days later, he left the Army. He told Read he couldn’t adapt.

The Army didn’t physically challenge Read, but it did mentally. He never got used to the cold or cleaning muddy vehicles in 2-degree weather. Read disliked manning the perimeter of the unit’s camp in the middle of the night, sitting in a fox hole with just a rifle and his thoughts, counting the minutes go by.

For about six weeks, Read ran 12 miles every afternoon. A commanding officer Read only remembers as Captain Valerio forced Read and another private to train for marathons with him. He didn’t know why he ran with Valerio, just that he had to. Read believes they were both new to the Army and didn’t meet Valerio’s standard.

The trio started around 2 p.m. each day but within seconds, Valerio blew past them. Read and the other private finished the runs together. At the next physical training test, Read sprinted the entire 2-mile course. He improved from the top 15 percent to second overall. Valerio said he taught them the “overload principal” — doing more than required to make it easier when you drop back down.

“It was just awful and I just said, ‘Man, when I get out of here I will never run again,’” Read said of running in the cold. “And I pretty much kept to that. I don’t. People say, ‘Well, you want to go for a run?’ No, I’m kind of shell shocked a little bit still from that. I don’t run to this day. I walk.”

He called home six months into his tenure, asking his grandmother if he could come home. She said no.

“Things got to get done and you got to do it,” Read said. “There was no other way. … Either you were going to do it or you were going to go to jail. Jail was not an option for me so I had to do it.”