SU’s NVRC hosts US Army veteran to discuss mental health, suicide prevention

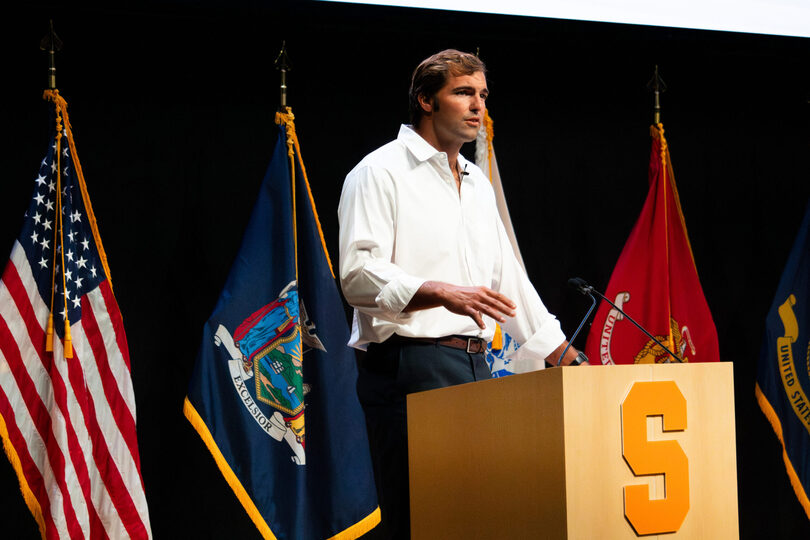

Alejandro Villanuevas served in the United States Army, which he said changed his views on mental health. The event aimed to discuss and destigmatize mental health, with a panel to highlight veteran voices and those affected by veteran suicide. Cassandra Roshu | Photo Editor

Get the latest Syracuse news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe to our newsletter here.

Content warning: This article contains mentions of suicide.

The National Veterans Resource Center at Syracuse University hosted Alejandro Villanueva, a United States Army veteran and retired professional football player, for a Suicide Prevention Education Talk Wednesday afternoon.

SPEd Talk is a storytelling event where speakers like Villanueva share their stories with the hope of shining a light on mental health challenges and resources. This is the second consecutive year SU hosted the occasion.

Villanueva, who was born in America and grew up in Spain, played football at The U.S. Military Academy at West Point and joined the Army when he was 22. He was stationed in Afghanistan in 2010, receiving a Bronze Star Medal for rescuing wounded soldiers under enemy fire. But he said he found life as a veteran different from what he expected.

“In my mind, I could not make sense of a lot of the things that I have just done,” Villanueva said. “And while I couldn’t make sense of anything, that’s when we started getting ready to go back again.”

SPEd is a national initiative to bring awareness to veteran suicide by discussing and destigmatizing mental health. Suicide among veterans accounts for nearly one in every five suicide deaths in the U.S. despite accounting for approximately 8% of the adult population, according to the SPEd website.

As a veteran, Villanueva said he’s seen firsthand the reality of his fellow military members’ lives in the aftermath of war. He said that while it was difficult to come back from combat, never cutting ties with his soldiers ensured that they got through it together.

His own mental health experiences were what led him to speak more about suicide prevention, Villanueva said.

“More veterans kill themselves from suicide than in action. The most powerful country in the world, and most of all mighty military in the world,” Villanueva said. “What can be said about such a military? What do we really say when we say thank you for your service, and they’ll kill themselves more than they have been caught killed by the enemy?”

After Villanueva spoke, SPEd Talk hosted a discussion with panelists, who either served or had family members that did. Among them were veterans and members of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, which aims to connect with others who have lost a loved one to suicide.

Army veteran Kenny Mintz said the special connections a group makes while serving are irreplaceable. Being a person to lean on for those suffering is one of the most important parts of his life, he said.

“I have a responsibility to those that I serve with,” Mintz said. “Even though I was a commander in combat and we went through this crucible event together, my commanding role has changed, but my responsibility to people has not.”

Kevin Swab, who attended the event and was a lieutenant in the National Guard, now serves as director of the Veterans Service Agency for Cayuga County. He said he sees challenges in connecting younger veterans with resources, which wasn’t always an issue, like during the height of the Vietnam War.

“The culture was obviously completely different than what we have today,” Swab said. “I see the younger veterans falling into what I consider to be kind of a trap, where they’re not coming together as easily.”

Austin Gleaton, a mental health therapist for the Department of Veterans Affairs, said he came to the SPEd Talk to educate himself since suicide prevention is part of his job description.

“I really love hearing personal stories about people’s relationships so I can implement that into my work,” Gleaton said.

Karen Heisig, a central New York area director for the American For Suicide Prevention, said people can reduce the stigma surrounding suicide by changing language patterns.

“Change the way you talk about it, such as, ‘died by suicide,’ not ‘commited suicide,’ Heisig said. “My husband did not commit a crime.”

Heisig said her husband’s death altered the course of her life. She also said the warning signs are real and should not be ignored.

“You’re human beings first. You have mental health, and if we don’t take care of our mental health, suicide is a real possibility and a real issue,” Heisig said.

For those struggling with mental health after serving or mental health in general, the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988 is available 24 hours a day.