Megan Thompson | Design Editor

Draper estimated that TMBC has provided tens of thousands of meals during the pandemic, including to local students who were left without school lunches during the transition to remote learning.

“It wouldn’t be uncommon to come down here and the line would be wrapped all around, down the street,” he said.

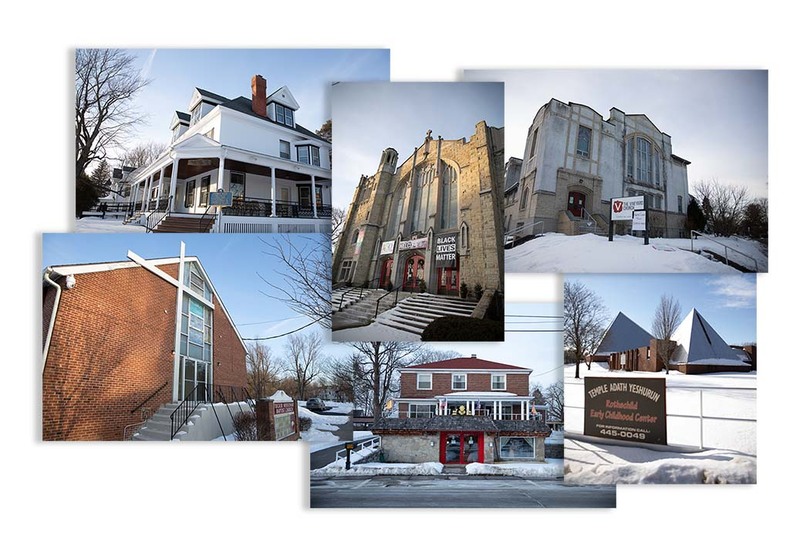

Since the onset of COVID-19, houses of worship across the country have become avenues to get food, vaccines and other forms of community assistance to neighborhoods hit hard by the virus. The same was true in Syracuse.

“The local religious communities really put forth very heroic efforts to help people,” said Michael Watrous, agency relations manager for the Food Bank of Central New York. “It was just really a tremendous outpouring of support.”

Though houses of worship have long been a part of the Food Bank’s distribution network, they became increasingly vital during the early days of the pandemic, when a surge in demand placed a strain on resources.

Houses of worship stepped up to meet those needs, Watrous said.

A glimpse at the Food Bank’s online Food Finder shows that a majority of its partners in Syracuse have religious ties — as many as 75%, according to Watrous. He attributes this to a shared mission of service that spans across different faiths and traditions.

“Many of them organized additional distributions. Many of them recruited additional volunteers,” Watrous said. “They’ve been really just invaluable.”

Watrous described houses of worship as community centers that are capable of reaching neighborhoods and populations other food distribution networks sometimes can’t.

For the Southside, one of those community centers was TMBC, where outreach efforts went beyond food distribution.

The church held pop-up vaccine clinics and helped residents apply for rent assistance. It continued offering up its sanctuary for funeral services, at a time when funeral venues in Syracuse were overwhelmed by both the rising tide of COVID-19 deaths and an onslaught of new restrictions.

“We were one of the places, because of the size of our sanctuary, where people had space,” Draper said. “We still tried to do that, to yet provide something normal for people, because when COVID hit people were dying at an alarming rate.”

Support from religious organizations went beyond food donations. In addition to collecting non-perishable food and menstrual products, Temple Adath Yeshurun launched a pen pal program with residents of a local nursing home who couldn’t have in-person visitors, said Sonali McIntyre, the temple’s Media and Public Relations Coordinator.

Wood remembers when social distancing restrictions forced UUMC to stop welcoming community members inside for a hot meal — an adjustment she said was difficult to make. To-go meals took the place of sit-down breakfasts as staff adapted to feeding hundreds of people in two or three hours.

But even in the pandemic’s darkest days, the staff continued to serve hot coffee. Wood insisted on it, if only as a sign to their neighbors that the church was still there to support them.

Strength in scripture

At Honess’ Vineyard Church — which has five locations in the Syracuse area — sanctuaries were replaced first with laptop screens, then with parking lots and playgrounds. Congregations would meet outdoors when safety and weather permitted, and virtually when they didn’t, until in-person worship resumed on a limited basis.

Honess remembers it as a time of uncertainty, when he had to put aside some of his favorite parts of the job. To get through it, he fell back on a familiar piece of scripture — a Biblical parable about two houses, one built on stone and the other on sand. In a storm, only the house built on stone, the stronger foundation, remains standing.

“That’s what I would come back to, that scripture ringing in my ears,” Honess said. He asked himself whether he would base his life on the stone — his faith — or on sand, the “shifting of culture and the shifting of politics and the shifting of this virus that happens every day.”

Several Syracuse faith leaders said they’ve also made pandemic-related decisions guided by scripture and religious principles.

In charting its COVID-19 response, Temple Adath Yeshurun relied on two guiding principles, McIntyre said. Those were pikuach nefesh — a Jewish principle that places the value and protection of human life above other religious commandments — as well as its own mantra, kulanu b’yachad, a call to unity meaning “we are together as one.”

Draper rattled off a series of Bible passages — Psalm 40, 2 Chronicles 7:14, Isaiah 40:31 — which he believes speak to the struggles congregants have endured during the pandemic and offer hope for the future.

Teich-Visco said that Tibetan Buddhists around the world turned to their faith during the pandemic, some praying to specific Buddhas known for their “power to quell pandemics and rescue people from disease.”

It wasn’t just the virus leaders sought spiritual guidance on. Honess, Draper and Wood all mentioned the role of scripture in approaching heavy issues, like politics and social justice, that may have divided congregations.

On Dec. 26, 2021, one year after his stint in the hospital, Draper addressed his church in person and live on Facebook.

He spoke frankly about his COVID-19 experience, the dangers of the looming omicron variant and the benefits of the vaccine. He also explained his decision to keep certain restrictions in place for in-person worship, even if some congregants disagreed.

“I want to do the things we used to do too, but we cannot, for your safety,” he said. “I want y’all to understand: COVID is for real.”

He added: “I love y’all, and death hurts.”