Cultures collide in Fumi Ishino’s art at Light Work

Courtesy of Light Work

Fumi Ishino is Light Work's September Artist-in-Residence, using his artwork to highlight differences between the United States and his home country, Japan.

Fumi Ishino moved to the United States from Japan to attend college, with no interest in photography.

“I didn’t know what I wanted to do. All I knew was that I wanted to get out of my country so that I could see my country objectively and see something new in a different country,” Ishino said.

He began practicing photography near 2008, drawing inspiration from cultural differences. Today, he’s taking up residency as Light Work’s artist in residence for the month of September.

The Artist-in-Residence Program invites participants to live in Syracuse for one month with a $5,000 stipend, an apartment and access to the Light Work facilities. Cjala Surratt, promotions coordinator at Light Work, said they get more than 1,000 applicants each year, which are carefully reviewed by curators, directors and staff to find the best fit of “emerging and underrepresented artists.”

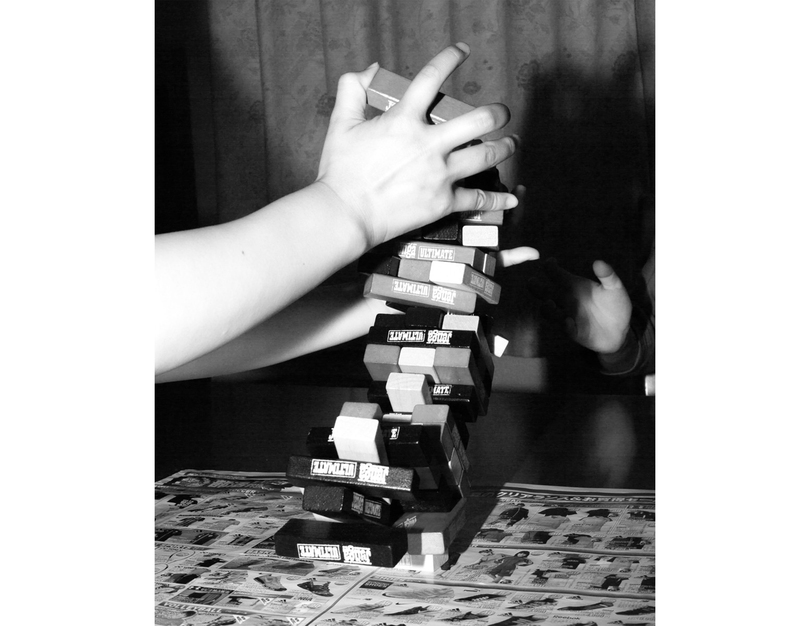

Ishino said because he’s from Japan, his values are not always the same as those in the U.S. This dissonance and “hierarchy of cultures” is prevalent in his latest work.

“I mix all the elements from different cultures, mainly from Japan and the U.S., and put it together and try to examine that hierarchy and different elements of the cultures,” he said.

Ishino said every year he improves his skill, which allows him to reflect on his own work.

“The more you learn about photography the more you realize you don’t actually know anything about it, so you need to learn more,” he said.

Mary Lee Hodgens, associate director at Light Work, said Ishino was chosen as a resident because his work was fresh and conceptually unique and also unique in the process he used to create it, which stuck out to her.

Inshino said that, so far, his experience at Light Work has been wonderful and the staff is helpful and knowledgeable. He is looking forward to finishing his print and hopes that he will have time to take advantage of the other resources Light Work offers.

He said he wants to explore the library at Syracuse University to do research — he doesn’t want just output from his art while he’s here, he also wants input from the university’s resources.

Most of the applicants are photographers themselves, she said, so they can expertly choose the residents. They’re focused on creating a diverse pool of artists, she added, but diverse in more than just race. They emphasize international diversity, including gender and age.

“When artists are given residency, there’s often a quid pro quo, but here there are no obligations to teach. We’re just here for support,” Surratt said.

Many of the artists have never been in an exhibition before, said Surratt, and the program helps “navigate the gatekeepers of the industry.” Even after their residence at Light Work, Surratt said they continue relationships with the artists, posting about past residents’ upcoming exhibitions or events on social media.

At the end of the program, each artist is asked to donate a piece of work to Light Work’s permanent collection, which is now composed of about 4,000 pieces of art.

Ishino’s work will be published in the annual edition of “Contact Sheet: The Light Work Annual,” which features pieces from residents each year.

“It’s not just a record,” Surratt said. “They are benchmarks in changes in technology to see how the profession has changed over time.”