After 9/11, this man went from a job in hospitality to being a glass artist

Alex Szelewski | Design Editor

Stephen Brucker spent 24 years working in the hospitality industry, for the Walt Disney World Company and US Airways. But after the 9/11 attacks, the airline industry collapsed, putting Brucker’s job on hold. He saw this as an opportunity to explore his passion in the arts.

“I took advantage of that and said, you know what, this is a sign — go back to school, do what you’ve always wanted to do,” Brucker said.

Brucker now lives and operates a studio in Camillus, New York, as a glass artist and sculptor. With nine shows in the past year alone, his work has been shown throughout exhibitions in New York state, including the Corning Museum of Glass’ World Glass Collection, where he also teaches glass blowing. Brucker’s next show, at the Brookline Arts Center in Boston, will run from March 17 to April 21.

Brucker started studying sculpture at State University of New York at Oswego in 2001 as an undergraduate, but wasn’t satisfied with the results of sculpting “very heavy materials” like bronze. He started gravitating toward lighter materials like plaster and paper, which led him to receiving his graduate education at the Rochester Institute of Technology in 2012. At RIT, he met Eunsuh Choi, a glass artist, and was fascinated and started glass working. Despite not having previous training in glass art, Brucker credits his time at RIT as the start of his glass art career.

“Glass art was a story that filled itself in, as a process of exploration and realizing what I didn’t want to create,” Brucker said. “I was searching for a material that was transparent and clear, and glass just has this very light and ethereal quality.”

Allison Duncan, special projects manager at the Corning Museum of Glass, teaches and coordinates programs on glass making techniques. She said she likes the “delicate complexity” of Brucker’s artwork.

“He transforms glass into dynamic organic structures,” Duncan said. “His sculptures encourage me to reflect on the beauty of the natural world.”

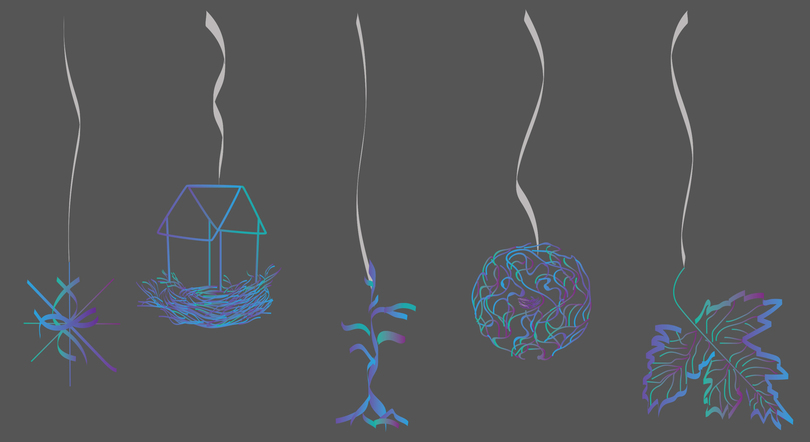

Courtesy of Stephen Brucker

When creating glass sculptures, Brucker heats small sections of glass and inflates them by shaping or blowing into it. Then, he assembles the pieces, which takes around a month, by stretching or cutting them into shape. As opposed to ceramics, painting or drawing, glass art is an art form that doesn’t require the use of hands. Glass sculptures are manipulated midair with a blowpipe.

“You cannot touch this material, which puts a different veil of technique across it because you have to imagine and envision what you’re going to be creating,” Brucker said. “It’s a medium that you can only touch when it’s cold after you’re done, so it’s very unique in that respect.”

The themes of Brucker’s glass sculptures are centered on nature. Brucker often studies structure and systems in nature, like the hydrological systems in hurricanes or the root structures in trees. The fragility of his glass art, Brucker said, represents the natural environment we live in. And he uses elements of that environment in his work.

“It’s tying that concept of when you see this tree, when you see this nest, when you see this tumbleweed, these are items in your daily life that are impermanent, fragile, and transparent,” Brucker said. “The whole concept is very transparent to me.”

But expressing these elements into art is also a challenge for Brucker. While working on a project centered on water, Brucker wanted to conceptualize the causes of hurricanes — heat, ocean temperature and wind — so people would understand these effects. Brucker eventually created a sculpture that tied in the situation of Hurricane Katrina, but struggled with illustrating that concept physically while he was making it.

“In those situations, the hardest part is to take that idea — that spark which usually comes when you’re driving or you’re in the shower — and say, ‘What does that look like?’” Brucker said. “How do I then translate that thought into a three-dimensional object and allow people to understand it?”

In addition to running his studio, Brucker teaches flameworking at the Studio of the Corning Museum of Glass in Corning, New York. He creates his own curriculum, and his classes are open to all ages.

Laura Quinn, an Irish glass artist, taught with Brucker at the museum over a summer. Quinn said she enjoyed working with Brucker, whose “positivity and caring nature” made for a great experience.

“His work ethic is to be admired,” Quinn said. “Stephen reaches for higher goals constantly, and with his unwavering enthusiasm convinces other artists to do the same.”

Brucker’s next workshop at the museum, from April 29-30, will be an introduction to borosilicate glass making, his specialty in the medium. He hopes to expand his classes and develop glass programs in central New York, where only a few higher education schools are teaching glass art. Brucker is also looking into creating a program at Syracuse University.

For Brucker, teaching at the museum is one of the most rewarding things about being an artist.

“To watch people come in and say, ‘There’s no way I could ever do this,’ but within a day, they enter the class and they’re producing a large amount of items,” Brucker said. “So I get to transfer knowledge to the them and watch those light bulbs go off because they get so excited.”