Justyn Knight builds off past struggles and pressure to stand out at Syracuse

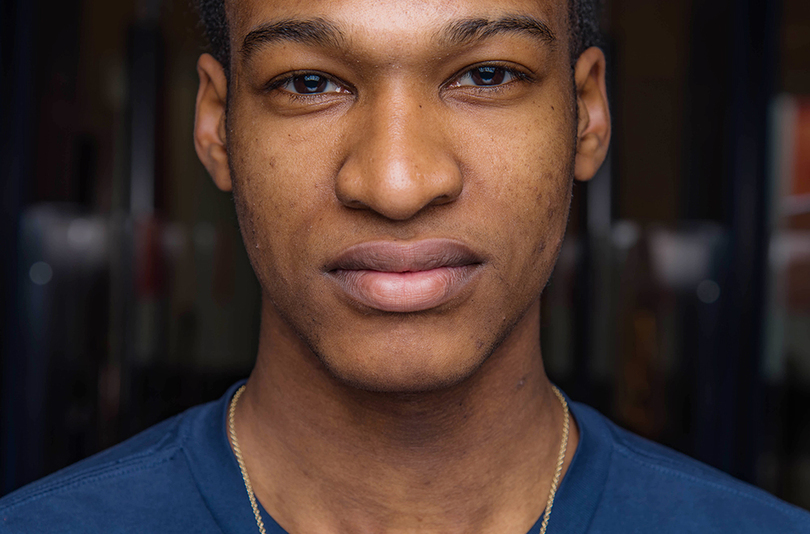

Phillip Elgie | Staff Photographer

Justyn Knight helped lead Syracuse to its first cross country national championship in 64 years. He gets a chance to replicate his success in track and field this spring.

The favorite had dropped off and it was Justyn Knight’s race to win. He led with 200 meters remaining in the Penn Relays, America’s oldest and largest track competition. It was the biggest race of the Canadian high school senior’s career.

He badly wanted to prove himself in the U.S. with tens of thousands watching. The entire Jamaican fan section cheered him on, he suspects, because he was the only black runner.

The Jamaicans cheered louder, urging Knight to hold off the hard-charging Andrew Hunter, a future Oregon signee. The 3000-meter race came down to a 50-meter sprint that normally takes Knight seven seconds. In the days and years that followed, he spent exponentially more time wondering why he couldn’t hold that lead.

To Knight, the Jamaicans’ “oooh” sounded like: “You let us down.”

“That one race sticks with me,” Knight said softly with his head down. “I never want to experience that race ever again. Winning is great and everything, but I really don’t enjoy losing.

“I do everything possible to not experience that feeling.”

Knight reflected in the Manley Field House bleachers, overlooking the track he now uses to make sure he avoids that feeling. Since that deflating race two springs ago, he has won numerous individual accolades, broken Canadian records and led Syracuse cross country to its first national championship in 64 years. SU head coach Chris Fox called him, “our Carmelo.”

The sophomore is celebrated for his dominance, which has come often in his first year and a half as a college runner. But it’s the losses, the pressure, that feeling, which have molded him.

“He hated (to lose),” his father, Anthony Knight said. “It’s never vocal. He has this fire inside of him.”

The “goofball” with the big laugh some teammates knew as “J-Money” changed after losses. Knight isn’t a poor-tempered loser, teammates and coaches said, but he’d go mute as losses gnawed at him.

“There were a couple times … he finished second,” former teammate Martin Hehir said. “He doesn’t like to lose, but we can usually get him turned around once he realizes our team just crushed everyone else.”

Knight’s brother, Jaryd, learned to leave Justyn alone. His mother, Jennifer, remembers “painful” car rides home from far-away, grade-school basketball tournaments that ended without trophies.

Those occasions were “bricks,” his mother said. She borrowed the term from an old family adage. Knight lost his starting spot on the basketball team in 10th grade. He struggled in the classroom. He didn’t find “his calling,” running, until halfway through high school.

At St. Michael’s College School in Canada, Knight felt content doing exactly what his coach Frank Bergin asked. Since running his first race in basketball sneakers and baggy shorts, he hadn’t needed extra effort. He won the league championship three weeks after he joined the team, set the Canadian junior record for the mile and became the 2015 Pan-Am Games cross-country champion. But the day after Bergin and Knight drove home to Toronto from The Penn Relays, he changed.

“He kept destroying workouts,” Bergin said. “I’d have to keep making up more stuff that I’d never given kids before. He just did it. There were workouts where I’d go, ‘Holy crap. You did that?’ … It got to the point where I was scared of what I was giving him.”

Bergin has coached world champions and Olympians. Knight, he said, is the best runner he’s ever seen.

After Knight picked Syracuse over Wisconsin, expectations followed him to central New York. The SU coaching staff scrapped redshirt plans when they saw Knight run despite his limited background. Top runners typically run about 60 miles per week, Knight was at about 35.

“I’m good at hiding it, but I get super nervous,” Knight said. “When I got nervous, all I thought was: ‘Justyn, you’ve created such a big name for yourself. You did everything you could in high school and in Canada and then you come here and coach is expecting a lot out of you.’ I hoped I didn’t disappoint them. … I didn’t want to waste the coach’s time (after not redshirting).”

The nerves didn’t surprise Bergin. He’d known Knight’s desire to not disappoint others since letting down the Jamaicans. Hehir and Colin Bennie, who often roomed with Knight on road trips, saw him fidgety before races. He worried about not knowing his competition because Canadian high school running hadn’t exposed him to elite American competition.

The third-year runner didn’t know things his teammates considered common sense, like what to eat or how far to run each day. He once asked Hehir how many laps made one mile. Knight confided in Hehir about his fear of disappointing. Hehir said Knight used the pressure as healthy motivation.

After a standout freshman season, which included winning ACC rookie of the year, he finished a disastrous 143rd at the NCAA finals.

“I cried all the tears out,” he said.

In 2015, Knight finished fourth overall in the NCAA championships. In one race, his shoe fell off but he won anyway. Through studying race results, he now knows more about other runners than anyone else on the team, Bennie said.

When you realize you just lost your shoe during a championship race? pic.twitter.com/H4pFRk8uDk

— Justyn Knight (@justyn_knight) May 18, 2015

Before a recent practice, Knight dribbled a field hockey ball. He smiled, bantering with two field hockey players about who was better. There were no signs of the vicious competitor who once passed three runners by listening to their ragged breathing and pushing the tempo when they were most vulnerable.

“His on/off switch is crazy,” SU assistant coach Jon Squeri said.

To understand why Knight hates losing and how he relentlessly comes back can be traced to his parents’ house.

Growing up, Knight’s father coached his basketball team. He tried to tire his players out by making them run suicides. As they kept running, some kids cried or doubled over.

“If I said, ‘Get on the line again,’ (Justyn) was just there,” Anthony said. “I could never tire him out.”

When Anthony was 13, he was cut from the basketball team and practiced the entire next year. When Anthony was 14, he became a starter. He won the award for his high school’s top athlete.

Years later, in Anthony’s home, another Knight graduated as athlete of the year. The yearbook commemorating it sat on a bookshelf. In that yearbook, toward the middle, is Justyn’s picture. To the right, above thanks to Bergin and others for unleashing his “hidden talent,” is his quote.

“A successful man,” it reads, “is one who can lay a firm foundation with the bricks thrown at him.”